This article was produced and published by the Water Education Foundation as part of its Western Water news. The Foundation can be found at www.watereducation.org. Our thanks to WEF for permission to republish their article.

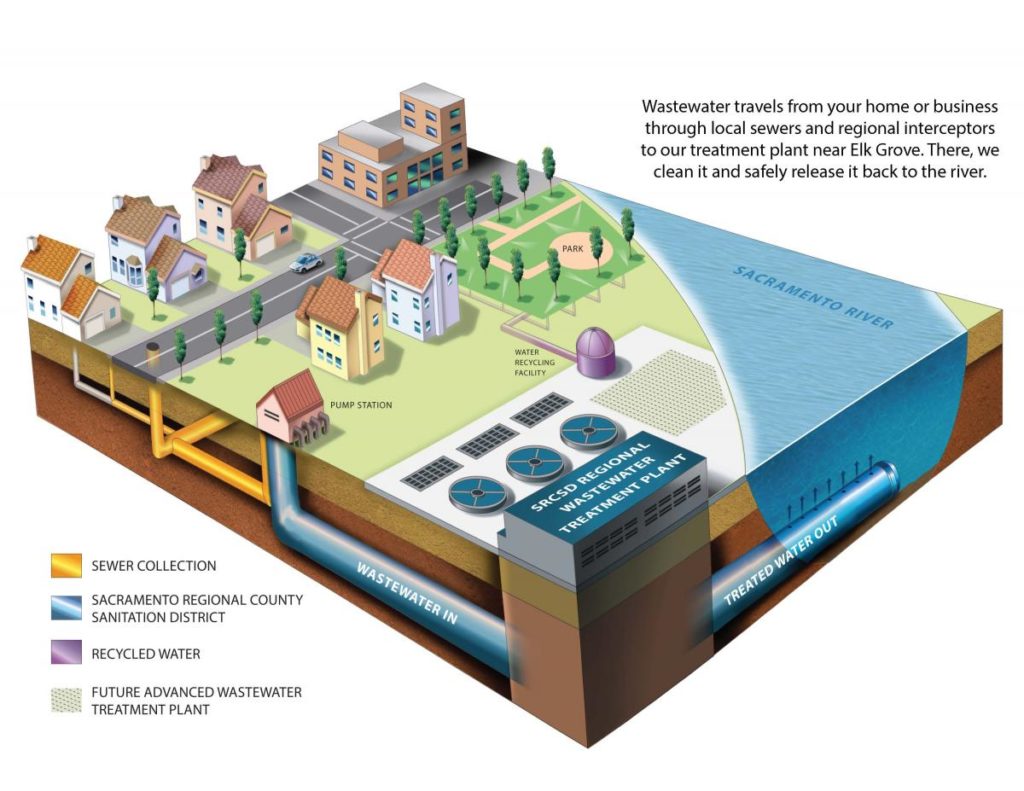

A description of the collection system and treatment plant by Sac Sewer.

Californians have been doing an exceptional job reducing their indoor water use, helping the state survive the most recent drought when water districts were required to meet conservation targets. With more droughts inevitable, Californians are likely to face even greater calls to save water in the future.

However, less water used in the home for showers, clothes washing and toilet flushing means less water flowing out and pushing waste through the sewers. That has resulted in corroded wastewater pipes and damaged equipment, and left sewage stagnating and neighborhoods stinking. Less wastewater, and thus more concentrated waste, also means higher costs to treat the sewage and less recycled water for such things as irrigating parks, replenishing groundwater or discharging treated flows to rivers to keep them vibrant for fish and wildlife.

It’s a complex problem with no easy answers. Some water agencies even have suggested the state needs to push more conservation efforts to outdoor water use rather than indoor use to keep wastewater flowing. For now, local sanitation agencies are beginning to assess how best to respond with changes in how they operate – and how they plan for a future that will inevitably include more droughts.

“Indoor water savings are good, but the flip side is, as you get lower [use] … at what point are you causing more harm than the benefit you are getting from saving those drops of water?” said Adam Link, director of operations with the California Association of Sanitation Agencies.

Link said his organization had heard anecdotal accounts of problems, but that they varied depending on location. Wastewater agencies generally handled problems through operational changes such as increased chemical treatment.

A recent report by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) quantified the problem, finding in a survey of wastewater agencies, that one-fifth of respondents indicated increased corrosion of collection systems due to declining influent quality.

There’s less flow in sewer pipes.

The PPIC’s report released in April, Managing Wastewater in a Changing Climate, said the wastewater treatment sector “is at a turning point,” with drought posing the biggest challenge. The report suggested action is needed to improve coordination between water suppliers and wastewater agencies to ensure that water conservation efforts in the urban sector can be accounted for as part of the short- and long-term planning on the treatment side.

“Wastewater managers would benefit from knowing which demand management strategies are deployed, when and where the strategies are being implemented, and how much indoor water savings are expected over time,” according to the report. It noted that the California Department of Water Resources and the State Water Resources Control Board could help facilitate better exchange of information and provide guidance for integrating water supply and wastewater planning.

Link agreed that as wastewater agencies plan for future treatment capacity and the projected demand for recycled water, they should be included in discussions about further reductions in water use — and how reduced flows affect the planning and sizing of recycled water projects. The state has set a goal of developing at least 2.5 million acre-feet a year of recycled water by 2030.

Rob Thompson, assistant general manager of the Orange County Sanitation District, said his agency has planned for changing flow patterns based on factors such as economic activity and the amount of rain received.

“When people talk about low flow, it’s really one of a plethora of items which are really about resilience,” he said. “We are consistently planning … with our operations, maintenance and engineering to deal with those changes.”

The district receives about 185 million gallons of sewage each day from more than 2 million people in north central Orange County (185 million gallons would fill a football field 515 feet deep). One hundred million gallons of that treated wastewater is put back to work to irrigate parks, schools and golf courses and help combat seawater intrusion.

The district’s collection system and manholes have been protected from corrosion since the 1960s and for the last decade, chemical treatment has been used to block formation of odorous and corrosion-causing compounds, said Thompson, noting that the district has been granted patents for its processes.

Treated wastewater flows in the Los Angeles River. These types of Wastewater discharges are important sources of water to help maintain river vitality (SCCWRP).

The 2012-2016 drought was the driest in recorded state history. The extent of the impacts from reduced sewage flows – corrosion, odor problems as sewage pools in neighborhood pipes and increased salinity – surprised some people. The episode highlights what’s needed in the future.

“We know the next drought is coming. This is our reality to manage and adapt to,” said Jelena Hartman, senior scientist with the State Water Board, at PPIC’s April panel presentation on the report.

Because many rivers rely on treated wastewater for water quality and flow, reductions in discharges can add to the environmental impacts on rivers when drought strikes, Hartman said. Less water flowing to rivers — whether from treatment plants, street runoff or stormwater flows — affects overall environmental quality.

“It’s not just water recycling,” she said. “We are talking about low-impact development, capturing storm flows and reducing urban runoff.”

Meanwhile, the drive to ratchet down water use in California begs the question of whether conservation efforts could eventually shift because of the impacts to the wastewater sector. A 2018 law sets indoor consumption goals at 55 gallons per person per day, with the figure dropping to 52.5 gallons in 2025 and 50 gallons in 2030. It’s up to water agencies to work with users to meet the goals.

In a 2017 white paper, Adapting to Change: Utility Systems and Declining Flows, California Urban Water Agencies (CUWA) noted that while saving water indoors is an important element of water management programs, more must be done to manage all future water demands. CUWA is an association of 11 major California urban water agencies.

“California policy on long-term water use efficiency should prioritize outdoor water use restrictions, which will have a lower impact on interconnected water systems, to achieve statewide demand management goals,” the white paper said.

Outdoor water use varies greatly in the state, accounting for as little as 25 percent of a household’s use in coastal areas and as much as 80 percent in the hotter inland regions.

On the environmental side, work is underway to quantify the impact of reduced discharges to surface waters. In Los Angeles, a coalition of state and local agencies are collaborating with the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project on a two-year study launched last fall to determine what happens when treated wastewater effluent and runoff usually sent to the Los Angeles River is diverted for recycling.

Researchers are looking at how vulnerable species and habitats along a 45-mile stretch of the lower reach of the river respond to flow reductions with an eye toward developing recommended flow targets by season and section of the river.

When drought returns to California and people do their part to conserve water, use levels will again drop, perhaps even to record-low levels. Wastewater treatment agencies will again be faced with even less flows. Thompson, with the Orange County Sanitation District, said agencies should use their regular retrofit and upgrade schedule to measure their resilience.

“You don’t design for one little problem,” he said. “You look at the overall condition of your treatment plant and look at opportunities to replace outdated infrastructure with more focused infrastructure that meets the new needs you are facing.”

The state, PPIC said, should help the wastewater sector and direct its funding assistance toward regional approaches to planning and research.

“The state also has a responsibility to evaluate its own policies for areas of conflict between water use efficiency, recycled water production and environmental flows,” the report said. “The state needs to be clear about the inevitable tradeoffs associated with these goals and help set priorities.”

There also needs to be better delineation between what’s happening with the long-term trend of reduced indoor water use and the impact drought has on that use.

“That is one of the unanswered questions,” Link said. “Is there going to be a bounce back [in water use after a drought] or is there where we are and what we have to plan for?”