It’s hard to imagine now, but many cities and counties in California provided no wastewater treatment at all prior to ocean discharge. The main types of treatment offered consisted of screening and/or sedimentation before discharge. In 1937-38, only three California cities, Laguna Beach, Oxnard, and Huntington Beach – utilized secondary treatment before discharge, with Laguna Beach employing the most advanced wastewater treatment process of the time: activated sludge.

Fig.1: This map offers a detailed snapshot of California’s wastewater treatment and effluent discharge into the Pacific Ocean around 1937-38. It was created to illustrate a paper on ocean discharge in the late 1930s. The paper and map later appeared as a chapter in ‘Modern Sewage Disposal,’ a book commemorating the ten-year anniversary of the Federation of Sewage Works Associations (now WEF) in 1938.

In a study on ocean discharge conducted in the late 1930s, members of the CSWA (CWEA), A.K. Warren and former Association president AM Rawn, highlighted the inadequacies in wastewater management planning in some older California cities. Many outfalls from the late 19th and early 20th centuries discharged into tidal waters at the most accessible locations.

For instance, both San Francisco and San Diego released untreated sewage, with San Diego also discharging settled sewage through various sea-level outlets. Warren and Rawn’s paper was later included as a chapter in ‘Modern Sewage Disposal,’ a book commemorating the ten-year anniversary of the Federation of Sewage Works Associations, now known as the Water Environment Federation (WEF).

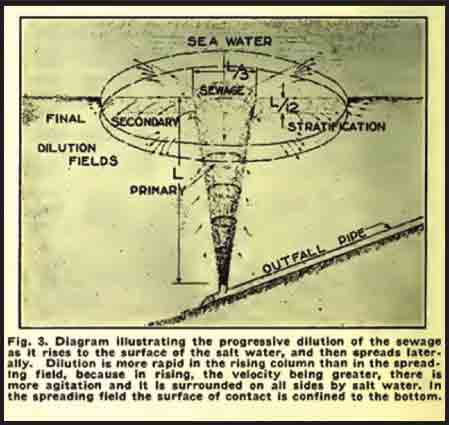

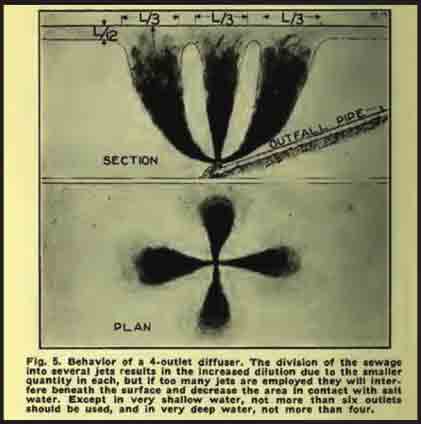

Rawn was recognized as an expert in ocean effluent discharge in California during the 1930s. He published articles and gave presentations on the design and construction of ocean outfalls and diffusers. Throughout his career, he worked as a consulting engineer on ocean outfall project planning for various agencies. The diagrams (Figs. 2 and 3) are from one of Rawn’s 1929 CSWA ocean discharge presentations, illustrating the dilution and stratification of wastewater effluent from an outfall pipeline, as well as from an outfall pipeline equipped with a diffuser. These were the days when “dilution as the solution to pollution” was considered an acceptable method for disposing of wastewater effluent.

Rawn’s 1929 CSWA ocean discharge presentations, illustrating the dilution and stratification of wastewater effluent from an outfall pipeline, as well as from an outfall pipeline equipped with a diffuser.

Rawn’s 1929 CSWA ocean discharge presentations, illustrating the dilution and stratification of wastewater effluent from an outfall pipeline, as well as from an outfall pipeline equipped with a diffuser.

Both Warren and Rawn acknowledged the necessity for better wastewater treatment and ocean discharge. In their 1938 review of California’s regulations for ocean disposal, they asserted that the current California regulations, if uniformly enforced, would eliminate most public complaints regarding ocean discharge. However, they also noted that the public would likely be reluctant to finance the necessary improvements to ensure beaches remain safe for recreational use, stating that it would be “unlikely that the sanitary conditions in those areas will significantly improve in the near future.” Additionally, they remarked that “…it is doubtful that the harbor waters of Los Angeles, Long Beach, or San Diego can ever be free from contamination to the extent required by law for bathing waters (recreational use).”

Reflecting on the ocean discharge situation in 1938 emphasizes the progress made in protecting California’s water environment. The increase in public awareness about the environment during the latter part of the 20th century, characterized by the implementation of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 and the 1972 Clean Water Act amendments, along with funding initiatives, has significantly improved the quality of California’s coastal waters.