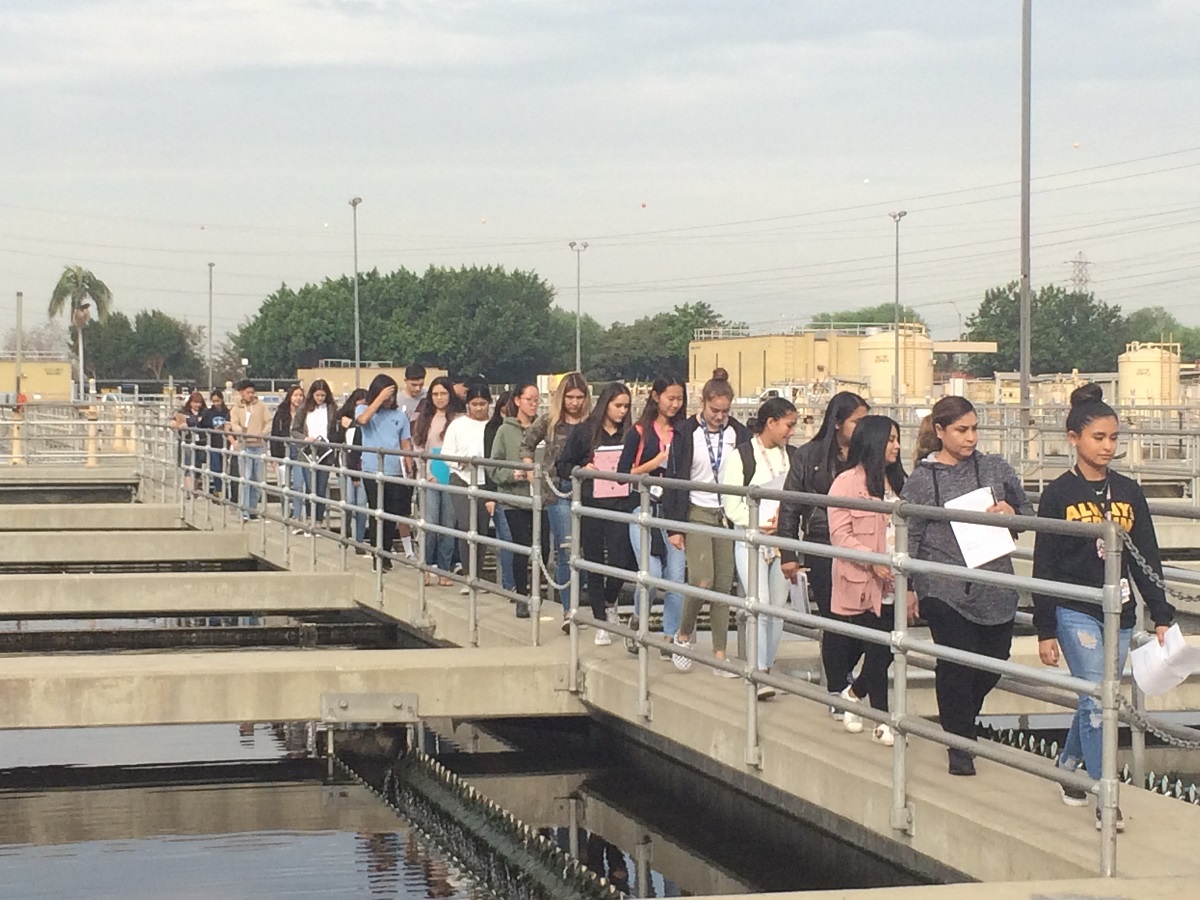

San Jose Creek Water Reclamation Plant (LACSD)

This article first-appeared in the Los Angeles City Historical Society newsletter. Reprinted here with permission.

The catchy phrase toilet-to-tap often appears in stories about recycling, despite recent widespread use of reclaimed water that is pumped into groundwater aquifers in Southern California. Even the New York Times in a recent story about recycling referred to the yuck factor, the “toilet-to-tap” fears of the uninformed.

So when did “toilet-to-tap” become a byword? The term was coined by Miller Brewing public relations people in December 1993 and was adopted by newspapers in the San Gabriel Valley during a Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts plan to expand its three decade groundwater replenishment program from the San Jose Creek Water Reclamation Plant.

The plan in 1993 was to build a nine-mile underground pipeline that would transport reclaimed water north from the Whittier plant, to the Upper San Gabriel Water aquifer running along the 605 freeway to the Santa Fe spreading grounds at the intersection of the 210 freeway in Irwindale.

Miller Brewing drew its water from drinking water near its Irwindale Plant. They were horrified by the prospect of customers identifying Miller Beer with recycled sewage water. For more than a year they had been holding up progress by bombarding the county with questions. According to Miller attorney, Terry O. Kelly, “The plan could increase the breeding ground of disease-carrying mosquitoes. It could foster health problems for infants, caused by nitrates in water. It could threaten sensitive plant and animal life. Pure and simple,” he said, “We don’t want the water changed. We don’t want the purity altered.”

Earle Hartling is the water recycling manager for the county and was designated the point person for the county’s counter attack to Miller as well as to caustic anti-recycling opponent, Dr. Forest S. Tennant. Tenant created a new non-profit, “Citizens for Clean Water.” Tennant, once an adviser to the National Football League on how its players could beat drug problems, in 1993, was operating a pain clinic in West Covina. He used his medical and political connections and his money to marshal forces against the plan.

He financed newspaper ads that, according to Hartling, suggested that “cancer, dementia, birth defects, hormone deficiency and cardiac disease” might arise from the reclaimed water.

In a recent interview, Hartling told me, “The full-on assault began at a hearing in December with the appearance of a gentleman who adopted a clown persona, E T Snell, the clown.”

Snell, dressed as a clown, his hair frizzy green and his face pale with white makeup, stood up and said “This is a plot by the trilateral commission secret world government to poison of the San Gabriel Valley.” Hartling noted that in his harangue, Snell pointed at him, and said, “if this water is so good why doesn’t this guy, pointing at Harling, drink it.” Hartling said, “I opened the bottle of water and drank it right in right in front of him. I was his personal demon.”

Miller Beer decided to focus most of their attention on Anthony Fellow, a member of the Upper San Gabriel Water Board, who supported the reclamation plan. Fellow’s memory was still vivid twenty-two years later as we talked about what happened. At the time Fellow was running for re-election to the water board. He said, “They would come in with toilets and all this stuff, during the election time, and the campaign was just horrible, they sent out flyers with my face on a toilet. They took out ads using sexy words together, ‘the horror of it, bodily fluids, etc.’”

Fellow spoke with pride about his battle with Miller. Although “Miller spent $120,000 to defeat me,” he said, “I came home and we started walking and on election night we defeated them three to one.” But the board did not vote for the expansion of the recycling program.

And the campaign backfired on Miller Beer.

The campaign was covered extensively by the local news media. Television stories prominently displayed Miller Beer bottles on a moving rack behind the anchor’s reports. The bottles were clear and Miller Beer was yellow. Hartling laughed as he recalled the reaction from viewers. “Sales of Miller plummeted, they shot themselves in the foot. It was such a big deal, Jay Leno made jokes for two weeks about the project.” Hartling said that Phillip Morris, the parent company for Miller, fired the legal team and told Miller to stop the campaign. He added, “Never put beer in clear bottles.”

At that point, Hartling said, Upper San Gabriel had exhausted their will and gave up. We fought to a standstill. The only one left standing was the one with the most money.” The bad publicity convinced the water board to halt the program.

Toilet-to-Tap re-emerged in the San Fernando Valley in 2000, when the city’s Bureau of Sanitation and the Department of Water and Power planned to take up to 60 MGD of highly treated water from the Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant through pipes to spreading grounds near Hansen Dam.

It was called the East Valley Reclamation Project. In 1990, after receiving approval from the necessary state and federal regulatory agencies, the DWP followed its usual pattern of public information. They held two public meetings, attended by no more than forty people, a few of whom questioned the project, because of their concerns about it promoting development in the valley. DWP also posted notices in local newspapers. There appeared to be no real opposition to the project.

But, in June 2000, all hell broke loose. The battle was begun by Encino homeowner Gerald Silver, who had attended the meetings in 1990 and was then opposed to the project because it might open up more development in the valley. Now, he took up the Toilet-to-Tap idea and met with reporters for the Daily News, claiming that the city was poisoning the water supply of the San Fernando Valley with tainted water, a toilet-to-tap scheme that should be exposed. The newspaper went on to feature almost daily stories about the potential harm to people who drank the reclaimed water.

Soon politicians picked up on the fear that was spreading about the reclamation project that had begun a few months earlier. They were urged on by then Councilman Joel Wachs who was running for mayor at the time. Wachs claimed that the DWP was trying to pull a fast one on the Los Angeles public, and that despite presentations to the council earlier, “I didn’t understand back then what the project would do.”

He went on to compare reclaimed water to aerial spraying of malathion. Wachs was soon joined by then State Senator Richard Alarcon who called a special meeting of the Senate Select Committee on Environmental Justice.

Alarcon claimed that communities had not been given enough facts about the project or how it would affect their drinking water “This is an option of last resort,” he said. Soon the Family Child Care Council of the San Fernando Valley, a Mexican-American health organization joined the opposition. “Children are not just little adults, and their exposure to this treated sewage water cannot be compared to adults,” said Mary May of the Child Care organization.

Faced with the political fallout, Mayor James Hahn formerly closed the program several days after Alarcon’s hearing. William VanWagoner, the DWP engineer in charge of the program said, “We spent a total of $55 million including hardware for recycling wastewater to recharge groundwater in Hansen Dam area.” With a laugh he added, “I spent slightly under one million bucks an acre foot—62 acre feet before it was shut off —I turned it on and it worked from October 1999 through June 2000.”

Toilet-to-Tap was a no-show when the West Basin Water District decided in 1995 to begin its own water recycling program. West Basin opened the first recycling plant with the wastewater from the Hyperion Treatment Plant, that was then receiving primary and secondary treatment before being discharged into Santa Monica Bay.

West Basin used advanced treatment that included microfiltration, reverse osmosis, and UV treatment of the water, a program that was similar to one begun in 2008 by the Orange County Sanitation District. West Basin’s plant in El Segundo is only a few miles from the Hyperion Treatment Plant.

The recycling plant began with 20 million gallons a day that was piped from Hyperion. Los Angeles charges West Basin approximately $300,000 a year. After the water receives treatment by West Basin, the district sells it to various customers: 35% is sold for well water and as a seawater barrier, with 80% of that water ending up as groundwater recharge.

The well water goes through microfiltration, reverse osmosis, and UV light with hydrogen peroxide. Irrigation gets about 12% and is sold to cities that use it for parks, including Torrance, Manhattan Beach, Redondo Beach, El Segundo, and Hermosa. Ron Wildemuth with West Basin told me that some also goes to Stubhub, a soccer field in Carson, some to Toyota and Honda for flushing toilets, some to Goodyear in their airfield in Carson, and Cal State Dominguez Hills uses it for landscaping. The rest of the reclaimed water, 53%, goes to refineries Chevron, Tsoro (BP) in Wilmington, Exxon-Mobil in Torrance for cooling towers, low pressure boiler water, high pressure water, also some landscaping.

There has been no outcry about toilet-to-tap from customers of West Basin. Currently West Basin buys 40 MGD of treated wastewater from Hyperion.

And there has been no outcry of toilet-to-tap from Orange County customers who are now receiving up to 100 MGD of reclaimed water from a program that began in 2008 with 70 MGD from the Orange County Sanitation District, using microfiltration, reverse osmosis, and is then dosed with hydrogen peroxide and bombarded with ultraviolet light to neutralize any remaining contaminants. When the County decided to recycle its wastewater in 1998, Ron Wildemuth was their public information officer. He led a massive information campaign and attended at least 2,000 community meetings where he held one-on-one discussions with schools, homeowners, community organizations, volunteer associations, and the environmental community. His staff went into overdrive, distributing slick educational brochures and videos and giving pizza parties.

He told me, “If there was a group, we talked to them. Historical societies, chambers of commerce, flower committees.” They also used phrases like “local control” and “independence from imported water. The county easily received widespread approval for recycling wastewater for eventual re-introduction to the water supply.

Orange County began with 70 MGD and recently increased their replenishment program to 100 MGD. About 2.4 million Orange County residents get their water from a massive underground aquifer, which, since 2008, has been steadily recharged with billions of gallons of purified wastewater.

People in the San Fernando Valley and the original planned recipients of the Tillman Reclamation Project—from Hollywood, downtown Los Angeles, Hancock Park and the Hollywood Hills—are still waiting for delivery of recycled water.

Reclaiming sewage water costs at least 20% less than imported water, and in some cases, as with West Basin, it is 30% less than imported water. The approximately 60 MGD of treated effluent from the Tillman Reclamation Plant in the San Fernando Valley flows into the Los Angeles River creating a pastoral vision for kayakers, wildlife and the environmentalists who envision a better Los Angeles River, and celebrate this odd rejuvenation of the river, which eventually, in dry weather, glides its way down the river bed. Wasted, it empties into the Santa Monica Bay.

Meanwhile the DWP appears to have embraced wastewater recycling for the future. It probably doesn’t hurt that because of the drought, Governor Jerry Brown has freed up more state money for water recycling projects: $800 million in low-interest loans approved by the State Water Resources Control Board in March 2014 and $725 million in a water bond approved by the state’s voters in November of 2014. And the Metropolitan Water District that provides water for most of Southern California recently announced plans to begin a recycling program of reclaiming approximately 150 million gallons of wastewater (sewage) a day. Although they did not mention toilet-to-tap, the phrase continues to resonate in news stories about cities and water districts throughout California now exploring their own plans to recycle their wastewater in an effort to fight the worst drought in California history that shows no signs of abating.

About the author: Anna Sklar is the author of Brown Acres and formerly an NPR reporter and public affairs director for the Los Angeles Department of Public Works. Like millions of other Angelenos, she lives on a desert by the sea.