AM Rawn (1888-1968) served as CWEA President from 1935-36

After the first World War, the population in the Los Angeles region began to grow at a rapid rate requiring a regional sewer system and infrastructure overhaul. The County Sanitation Districts of Los Angeles County (CSDLAC) was formed in 1923 when the “County Sanitation District Act” was adopted by the State Legislature. At this time, a young man named Abel Milizer “A M” Rawn Jr. moved to Los Angeles and began a lifelong career with the CSDLAC.

Rawn rose to a position of influence and prominence in the planning and implementing of wastewater treatment and disposal in one of the country’s major urban areas through grit and determination. His career is a shining example of the career one can attain by following the hands-on approach of “discere faciendo” (learning by doing) first championed by John Dewey (1938).1

Before moving to Los Angeles, Rawn worked on Reclamation Service projects for 10 years. He had concluded that the “heyday” of significant federal irrigation projects was ending because the cost of developing water for such projects was becoming unaffordable to agricultural users without substantial subsidies.

Between 1921 to 1923, Rawn found it challenging to find work as a civil engineer, especially with the job market saturated with returning military personnel. A friend, Walter E. Jessup, introduced him to the Los Angeles County Engineer and Surveyor, who was organizing a group under the direction of Albert Kendall (A. K.) Warren to address the needs for surface street drainage, flood control, and wastewater collection, treatment, and disposal.

Rawn was hired as an engineer and assigned to the County Surveyor to perform the preliminary survey and drafting work needed to incorporate some Los Angeles County areas into a large wastewater district.

Rawn’s employment with the County proved to be a momentous event for his career, the wastewater field, and sanitary engineering in California. After the Sanitary District Act of 1923 was passed, Warren was charged with organizing and forming the County Sanitation Districts of Los Angeles County (CSDLAC) and became its Chief Engineer and General Manager.

Rawn quickly recognized that one of the most valuable services he could perform would be to support Warren’s effort in establishing the Districts. Rawn started by meeting with the local stakeholders, civic organizations, and community leaders within the newly forming sanitation districts to explain the purpose and benefits of the CSDLAC. It was necessary to raise bonds to finance the new infrastructure required for wastewater collection, treatment, and disposal, and Rawn proved to be quite adept at this type of public outreach.

His out reach efforts, combined with his design expertise, led to his promotion to CSDLAC Assistant Chief Engineer/General Manager in 1924 and then, after Warren’s death in 1940, to Chief Engineer/General Manager. He would dedicate the next 28 years to advancing the fields of wastewater collection, treatment, and disposal by applying his technical, administrative, and leadership skills to more fully develop the regional district concept pioneered by Warren.

The CSDLAC plan for wastewater disposal involved selecting a site to construct a “joint” plant to treat the wastewater from several CSDLAC districts. This plant, located at the Bixby Marshland in Carson, Calif., allowed for ocean discharge of treated effluent at some point along the Palos Verdes coast. The plan also included the construction of a temporary activated sludge treatment plant that would discharge treated effluent to a slough while an ocean discharge point was selected and constructed. Working with H.R. Bolton, Rawn developed an outfall plan that incorporated a tunnel underneath Palos Verdes to a discharge at White’s Point. CSDLAC subsequently adopted this plan.

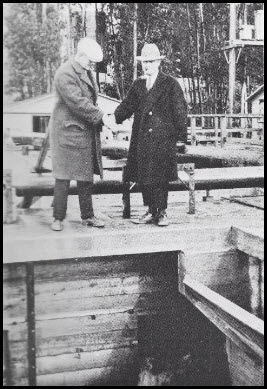

Rawn (left) with A.K. Warren during the start-up of the CSDLAC temporary activated sludge plant, February 4 1928

Even though ocean discharge following primary treatment was the selected wastewater disposal method employed by the CSDLAC, Rawn was interested in treating wastewater to a higher degree to reclaim the water for reuse. One can glean this interest, savored by his reservations about reuse, from a reading of his Oral History, viz: He “realized that the wasting of large quantities of water as in sewage and industrial waste, if it could possibly be reclaimed and reused, was an extremely important thought and idea in the development of southern California…”

But “even with the Colorado [River] coming into the picture, there might again be a shortage of water, but that until there was the idea of reclaiming water directly from sewage for unrestricted use was not at all practical.”

And “…I still stand by my belief that water imported from a distant river source…is far more desirable than any which may be reclaimed from sewage, and that extensive use of sewage water for anything excepting irrigation and industry will not be chosen if it can be avoided.”

How prescient were these words? Combined with Rawn’s efforts, the ideas that they convey led to the construction of the first CSDLAC inland wastewater reclamation plant at Whittier Narrows, commissioned in August 1962, some four years after he retired from CSDLAC.

Besides the responsibilities for wastewater collection, treatment, and disposal, the CSDLAC eventually became tasked with disposing of all types of solid wastes. Until the late 1950’s most residences in Los Angeles County had a backyard incinerator for burning “non-perishable” solid waste. It was thought that the deteriorating air quality in the Los Angeles Basin was largely due to the emissions from these backyard incinerators. In 1950 Rawn recommended that these incinerators be replaced by trash and garbage collection, followed by disposal in the “cut and cover” incinerator ban. This was implemented on Oct.1, 1957, and the disposal of solid waste became, and continues to be, CSDLAC’s responsibility.

Rawn was born to Abel Rawn and Emma Leet Rawn in Dayton, Ohio, on Nov. 2, 1888. In 1909, after graduating high school, Rawn decided to go by the initials A M (with no periods after the initials).

Rawn intended to drop out of high school in his senior year after taking a summer vacation job with Illinois Central Railroad as a survey instrument man. The railroad job paid $75 a month and was considered “big money for a young man to earn.” However, he was eventually “recruited” back to the high school because his school needed a fullback for their football team. He found that he was mathematically inclined, so he took as many math classes as possible.

Rawn’s vacation work on the railroad convinced him that he wanted to become a civil engineer. After receiving his high school diploma, he continued to work on railroad construction, first in Mississippi and Louisiana and subsequently as a construction inspector in New Orleans.

Although he attended college, Rawn felt his association with university graduate engineers while working on railroad construction taught him more than his “sketchy” college years, where he expended more energy playing football and baseball than on his studies. To paraphrase him, these engineers’ textbooks eventually became his textbooks. Through a combination of work experience, self-training, and mentoring, Rawn was able to pass federal engineering exams, and in 1912 he joined the United States Reclamation Service (now the Bureau of Reclamation) as a civil engineer.

During his 10-year tenure with the Reclamation Service, Rawn was assigned to major irrigation system projects, first as a surveyor in charge of field crews, then as a topographical draftsman, and finally as a principal draftsman. He completed minor design work for irrigation system headgates, flume outlets, diversion gates, pipelines, and prepared cost estimates for canals, large pipelines, and diversion works.

At the Reclamation Service, Rawn continued his approach of learning from more experienced engineers. This type of experience and training served him well as, later in his career, he transitioned from irrigation to wastewater projects. He often emphasized that his understanding of mathematics, materials, and design work were enhanced by his association with engineers on the job.2 He recounted that he became a professional engineer “by way of the school of hard knocks” rather than a college education.

Rawn participated in both World Wars. In World War I, first as a corporal in the 319th Engineers, then as a second and first lieutenant in the 605th Engineers’ American Expeditionary Forces. During World War II, he was called on by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to serve as an ex-officio director of the Sewerage and Sanitation branch of the War Production Board and as a member of the Federal Water Pollution Control Board.3

When World War I ended, Rawn returned to the Reclamation Service and was assigned to projects in Idaho. It was there he met Edna Louise Robinson, a junior clerk for the Reclamation Service. They were married on June 8, 1920.

Besides his illustrious career with CSDLAC, Rawn extensively served the government and profession.

President of the Water Pollution Control Federation, 1944

For example, he was a charter member of the California State Water Pollution Control Board (1953-1971) and a member of the Federal Water Pollution Control Advisory Board (1951-52). He was a member of numerous consulting engineering boards in the USA (Portland, OR; San Diego, CA; Orange County, CA) and overseas (Vancouver, B.C.; Canada; Auckland, New Zealand).

Rawn was active in many technical societies, including the California Sewerage Works Association (president 1935); the American Society of Civil Engineers (honorary member, 1958; Rudolph Hering Medal, James Laurie Prize); the Los Angeles Engineering Council and Founder Society (president, 1940); the Water Pollution Control Federation (president, 1944); the American Water Works Association; and the Society of American Military Engineers.

Rawn spoke of the importance of professional involvement, saying “…I would emphasize that any engineer, at least a civil engineer…who fails to identify himself with and attend the meetings of the society which represents his branch of the profession is doing himself a great disservice because it is at these meetings that those problems which are pressing in the area, and particularly those of the nature for which the man’s professional background qualifies him, are being discussed in detail and in the language which he understands.”

1 John Dewey “Experience and Education” Kappa Delta Pi, 1938, ISBN 0-684-83828-1.

2 Peterson, Erich, “A. M. Rawn Sanitary Engineer” transcript of an oral history conducted by Eric Peterson 1966 (Oral History Program, University of California, completed 1969), p. 7.

3 Chi Epsilon, National Honor Member Bio Page