Paula Kehoe, Director of Water Resources for SFPUC, and member Blue Ribbon Commission on Onsite Non-Potable Reuse.

The path to on-site non-potable water reuse has been beset by roadblocks, but a new initiative is removing them to clear the way for more efficient water management.

Whether challenged by multiyear drought, extreme flooding, impacts due to a changing climate, or increased demand on water supplies due to population growth, water utilities across the nation are taking on new approaches to manage local water supplies and increase resilience. Through a “one water” approach, all water — drinking water, wastewater, stormwater, graywater, and more — is managed as a resource that should be utilized and valued across all stages of the water cycle.

As utility leaders, city officials, and the general public embrace innovative, integrated, and inclusive approaches to water use, the opportunity to utilize alternate water sources (e.g., roof runoff, stormwater, foundation water, blackwater, and graywater) for nonpotable uses is great. Water that we normally let run down our drains or through our streets into receiving waters has untapped potential to meet non-potable needs such as cooling buildings, irrigating landscapes, and flushing toilets, and offset valuable potable water supplies. The key is applying the right water to the right use.

Nov 8th, 9:00-4:30pm at the TreePeople conference center in Los Angeles. Click here to learn more >

On-site non-potable water systems are changing the way we think about matching water supplies with the right use. On-site nonpotable water systems collect wastewater, stormwater, rainwater, and more and treat it so that it can be reused in a building or at the local scale for non-potable needs. These systems are usually integrated into the city’s larger water and wastewater systems, while providing more sustainable management of water.

What originally began as a response to drought-driven conservation needs in urban cities, on-site non-potable water systems have increasingly gained interest as an element of long-term, resilient, and sustainable water supply planning. Other benefits can include stormwater pollution reduction, extending the capacity of existing infrastructure, potential reduction in energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions from collecting and treating water at the source, and environmental stewardship.

If proven technology is available and the benefits are evident, why, then, haven’t we seen more widespread implementation of these systems?

Breaking Barriers

First, communities are challenged by the lack of guidance on how to develop permitting processes, management, and oversight programs for these systems. That’s why the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) convened the Innovation in Urban Water Systems meeting in May 2014 with support from the Water Research Foundation (WRF) and the Water Environment Research Foundation (WERF) to share knowledge and best practices, discuss barriers in implementing on-site non-potable water systems, and identify model programs to learn from. The meeting was the first of its kind, bringing together a range of water utilities, public health agencies, and research institutions from across North America to develop recommendations to help communities overcome policy barriers to implementation. The meeting led to the development of the Blueprint for Onsite Water Systems: A Step-by-Step Guide for Developing a Local Program to Manage Onsite Water Systems.

The Innovation in Urban Water Systems meeting also uncovered that the most critical issue communities face with implementing and scaling on-site non-potable water systems is the lack of guidance on developing water quality standards and monitoring strategies to adequately protect public health. Currently, there are no national standards or guidelines for on-site non-potable water systems in the U.S. While some states may have limited standards in place today, there is wide variation in existing water quality criteria.

To further chip away at this barrier, we partnered with National Water Research Institute (NWRI) to develop recommendations and guidance for treatment requirements that ensure public health protections and to develop a management framework for the appropriate use of on-site treated water for non-potable applications. NWRI convened an Independent Advisory Panel to establish recommended strategies and standards for management, monitoring, permitting, and reporting by using a risk-based approach that was protective of public health. The research was published by WRF and the Water Environment & Reuse Foundation (WE&RF) as Risk- Based Framework for the Development of Public Health Guidance for Decentralized Non-potable Water Systems.

The report provides information and guidance through a risk-based framework to help state and local health departments develop on-site non-potable water systems that are adequately protective of public health. The framework includes risk-based performance criteria that are consistent with the most advanced and protective public health standards to ensure safe water is delivered at all times. Furthermore, the framework also fits the Water Safety Plan approach promoted by the World Health Organization. Unlike current limited standards for on-site non-potable water systems that often rely on end-point assessment of water quality, the risk-based framework focuses on a systems-based approach to setting water quality targets that will help reduce the public’s exposure to pathogens. While this framework is new for on-site nonpotable water systems, the approach is based on widely accepted practices for both drinking water and potable reuse.

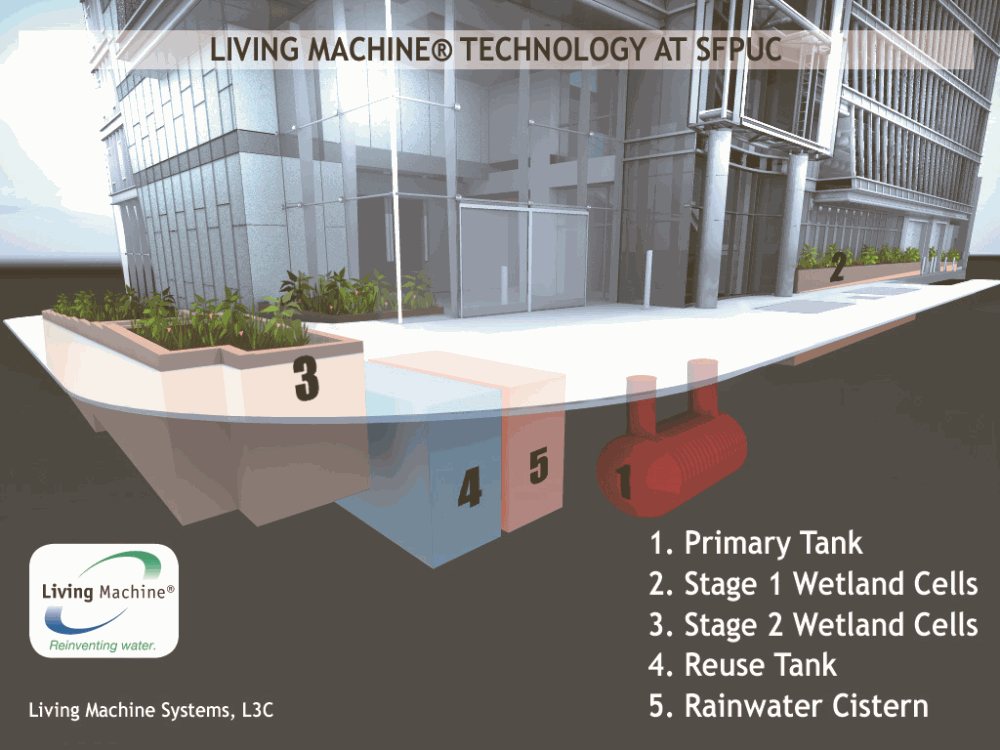

The “Living Machine” graywater treatment system at the SFPUC headquarters in downtown San Francisco.

Ideas Into Action

With this research as an essential tool, our attention is now on translating these risk-based standards into policy guidance and frameworks that support local implementation of this sustainable water strategy. To do this, the SFPUC partnered with the US Water Alliance, along with WRF and WE&RF, to convene the National Blue Ribbon Commission for Onsite Non-potable Water Systems from 2016 to 2018. The National Blue Ribbon Commission is composed of over 30 representatives from public health agencies, water utilities, and municipalities from 10 states and the District of Columbia. In addition to serving as a forum for collaboration and knowledge exchange, the commission is also charged with crafting a state guidance and policy framework that recommends mandatory water quality criteria for non-potable water systems that can transfer from state to state. Using the risk-based public health research as a guide, the model state guidance will focus on creating consistency in the elements of an oversight and management program including water quality performance, monitoring, and reporting requirements, as well as presenting various implementation pathways to establishing a successful local program. Additional items that will be included in the model state guidance are templates for an engineering report and O&M manual and other requirements for design, construction, and operation. With this document, states will be able to customize a guiding policy that is consistent with public health standards across other states, but that honors local context and meets local needs. The commission’s goal is to work with our respective states, and others, to adopt similar guiding policies in order to address this barrier and advance local implementation of these systems.

The onsite “Living Machine” treating water at SFPUC.

However, even with addressing this policy barrier, other challenges that have inhibited the development of on-site non-potable water programs persist, one of which is generating interest in and demand for on-site non-potable water systems by developers and city officials. City officials need to better understand how on-site non-potable water systems can be a tool of flexibility within smart growth and retrofitting plans and policies. As new facilities are being constructed, city agencies can promote incorporation of on-site non-potable water systems and can set policies that incentivize, or even require, their integration. At the same time, developers need to better understand the connection between sustainable water management and business productivity and stability. By incorporating these systems, building owners can reduce water-related hard costs, as well as meet sustainability targets and minimize indirect risk exposures. However, developers need more data that demystifies the risks and demonstrates the return on investment. As more data that quantifies the benefits of these systems is available, the more it will shape market-driven and policy-driven demand.

And finally, as water challenges and our strategies for addressing them evolve, so should the water utility industry. Fundamentally, the utility business is changing as we introduce new types of infrastructure and innovations to centralized water and wastewater systems. Despite growing interest in this innovation, it has not been without concern for loss of revenue or loss of control as more commercial and industrial customers deploy these systems. How can utilities quantify the benefits beyond water saved? How can utilities continue to recover costs, reduce risk, and maintain system control? A report being developed by the National Blue Ribbon Commission will help answer these questions by demonstrating the potential business opportunities for public utilities and municipalities in the implementation of on-site non-potable systems. The commission is focused on helping utilities confront these concerns in order to focus on the ways in which utility business can benefit from integrating on-site non-potable water systems with centralized infrastructure.

As the field of on-site non-potable systems evolves, the commission is committed to staying abreast of new science and approaches that support on-site non-potable water systems, as well as identifying additional research needs in the field. An additional deliverable of the commission is a research agenda that will further advance the field.

As with any emerging innovation, the best way to evoke change is to model it. That’s what the SFPUC and our two dozen public utility and public health agency partners are trying to emulate. We hope that through our efforts on the National Blue Ribbon Commission, we can break down policy barriers, demystify the unknown, and pave the way for future research. We’ve been able to forge great progress together and, with expanded partnership from other agencies, water industry organizations, and various stakeholders, we can continue to advance the field toward a more sustainable water future.

This column was originally published on WaterOnline.com