As regular readers of my blog are likely aware, this week EPA announced proposed Maximum Contaminant Limits (MCLs) of 4 ppt for PFAS in U.S. drinking water utilities.

I’m a social scientist, not a toxicologist or engineer. I can’t speak to health risks or the benefits of regulating PFAS. I can’t address the feasibility of PFAS filtration or disposal technologies. I can speak to the political and organizational impacts that are likely to accompany implementation of new PFAS rules. With those caveats in mind, here’s my incoherent brain dump thoughts on the proposal:

It’s a great week to be an advanced water filtration manufacturer!

Meeting the proposed standard nationwide will be costly, but how costly isn’t quite clear. Initial estimates of compliance costs for the proposed PFAS rules vary widely. EPA’s $772 million annual cost seems to be rosiest estimate; the AWWA’s $3.8 billion annually is the highest I’ve seen. People I trust tell me the pricetag might end up a lot higher.

I don’t have the expertise to evaluate the validity of these estimates, but I can put them in context. Total annual drinking water rate revenue in the U.S. today is about $70 billion. So based on current estimates, utilities will need to raise revenue by something like 1-5% to comply with the new rules. That’s in addition to increases already slated to pay for replacements, upgrades, operations and maintenance.

Thing is, those costs won’t fall evenly across the country. Data from Wisconsin (among the leading states in tackling PFAS) suggest that the vast majority of community water systems have have PFAS levels orders of magnitude below the proposed MCL. So for those systems, there won’t be much impact beyond increased monitoring and reporting costs. Many (maybe most?) Americans won’t experience noticably higher water bills due to this rule.

A small minority of water supplies have very high levels of PFAS contamination. These systems face staggeringly high costs to eliminate PFAS from drinking water. Many of these are in small or shrinking communities where costs could be crippling, but severe contamination demands action—we’ll need to find a way to help with grants and subsidies.

But I keep thinking about places with very low but detectable levels of PFAS (Madison, Wisconsin, for example). What will it take to meet EPA’s proposed standards in those communities?

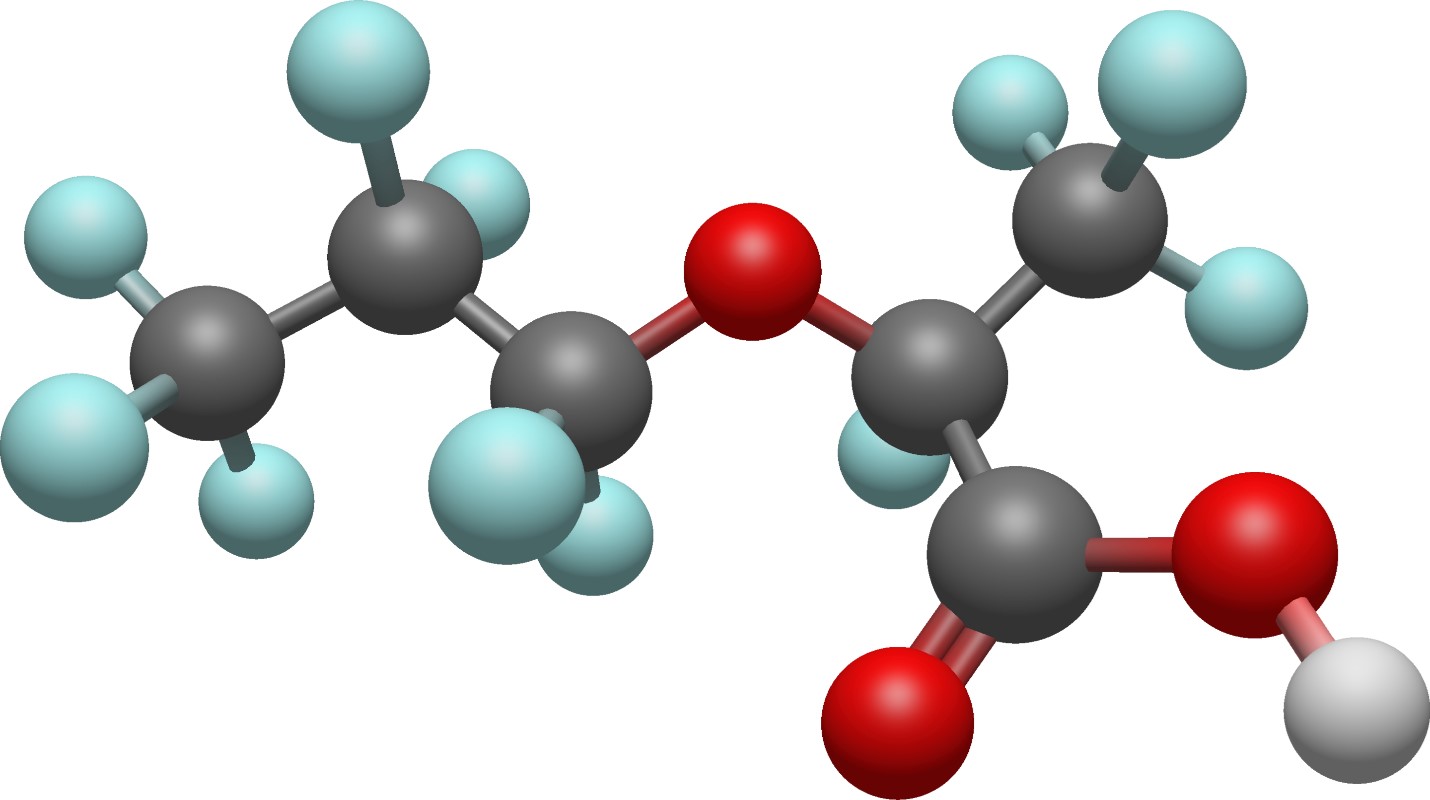

This one is hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (GenX). It’s not as cute.

The increased costs that accompany aggressive PFAS requirements will cause some local government utilities to defer other investments in an effort to minimize or avoid rate increases. I’m worried about continued neglect of water infrastructure generally and distribution systems specifically. Distribution system failures create immediate health risks from biological contaminants (to say nothing of disruptions to homes and businesses, or the risks to the safety of water operators). Even monitoring requirements will be onerous for very small utilities. In places where PFAS treatment is required, high costs risk crowding out other needed investments.

In theory, all utilities are subject to the Safe Drinking Water Act. In reality, compliance and enforcement vary considerably. The leaders of large, resource-rich utilities may grumble about PFAS rules, but eventually they will come into compliance.

Of greater concern are the numerous smaller, poorer systems that will alway struggle to comply because they lack organizational capacity. No amount federal funding and technical assistance can make these small systems sustainable in the long run because the chief limitation is organizational capacity. There are only two possible long-term outcomes for small systems faced with significant ongoing PFAS costs: 1) small utilities will consolidate in order to gain the organizational capacity they need to meet the new rules; or 2) small systems with PFAS contamination will limp along in more or less perpetual violation, while regulators turn a blind eye or move the goalposts for them. If the past is any guide, #2 is the more likely scenario.

This one is a balloon wiener dog. Cute!

Large investor-owned utilities (IOUs) are well-positioned to tackle PFAS, and so stand to grow their market share as a result of aggressive PFAS regulation. Empirical research consistently finds that IOUs boast stronger compliance with environmental regulations compared with local government utilities. One reason that IOUs perform so well is that regulatory institutions give them strong financial incentives to invest in the facilities needed to meet high standards, but insulate them from the political costs of high prices.

Faced with the technical and ongoing financial challenges of meeting PFAS standards, many municipal leaders may throw up their hands and get out of the water business. IOUs can acquire and operate many of those systems. Customers will pay markedly higher prices, but also will enjoy PFAS-free water. Rigorous PFAS regulation might even spark a privatization boom. That would shift pricing and investment decisions from city halls to state regulatory commissions. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. Indeed, there’s a good argument that privatization is the surest way for small and medium-sized communities to meet the regulation. But the implications of the proposed PFAS rules for privatization seem to have gone largely unnoticed.

The proposed PFAS standard is a full employment program for environmental attorneys! Environmental activists will sue regulators and utilities. Utility organizations will sue regulators. Everyone will sue chemical manufacturers. In the end, judges who have no expertise in chemistry, toxicology, environmental engineering, economics, or utility management may end up deciding the fate of PFAS regulation in the United States.

Dr. Teodor’s research stands at the nexus of politics, public policy, and public management.

He works mainly on American environmental policy design, evaluation, and implementation. This line of research includes explorations of public vs. private utility management, and regulatory implementation as a matter of environmental justice.

On the public management side, his work emphasizes professional labor markets as and predictors of innovation and organizational performance. His book 2011 book Bureaucratic Ambition (Johns Hopkins University Press), argues that career concerns shape organizational innovation and democratic governance. And his 2022 book The Profits of Distrust (with Samantha Zuhlke & David Switzer, Cambridge University Press) links the meteoric rise of the commercial drinking water industry to distrust in government and a broader withdrawal from civic life.